If you’re going to invest in an Old Testament commentary to help you with preaching, your best bet is to choose one on Isaiah. It comes up so frequently in the related Sunday lectionary and is rich with meaning and imagery. In general, the ‘best commentaries’ website provides a really useful overview of commentaries by book, as it tells you what kind they are (technical, pastoral, etc).

For what it’s worth, I would recommend getting hold of one theological commentary and one technical commentary. That way, all bases are covered. My recommendations are:

Williams, Jenni. The Kingdom of our God: A Theological Commentary on Isaiah. SCM Press, 2019.

Watts, J., Isaiah 1–33 / 34-66 Word Biblical Commentary (Waco: Thomas Nelson, 2005) - in two volumes. Watts doesn’t subscribe to the idea of ‘three Isaiah’s’ which makes him unusual, but this commentary is very good at textual detail.

Now - on to this week’s text!

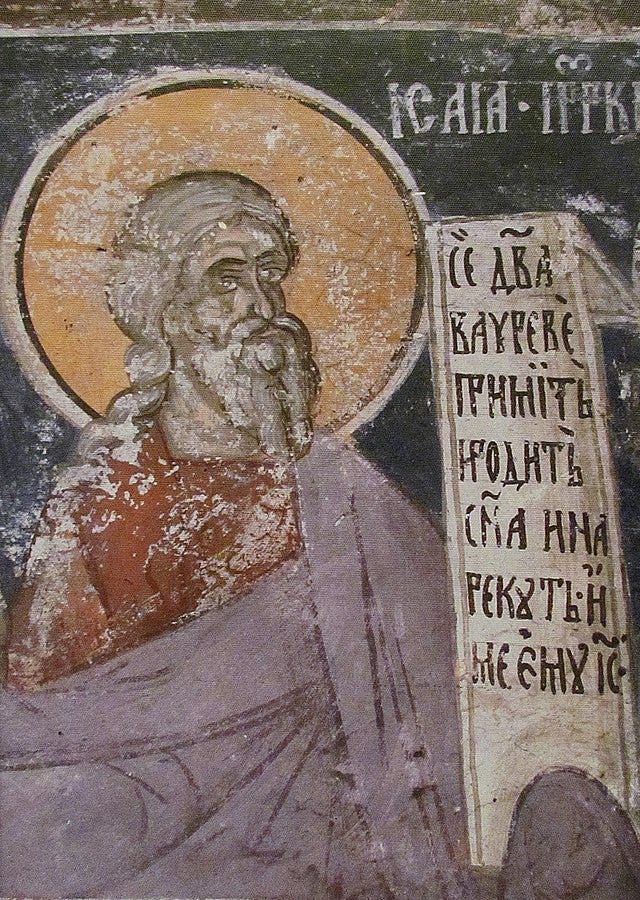

Isaiah the Prophet, fresco in Hermitage near Studenica, c. 1618

This portion of Isaiah comes from the latter part of the book (third/trito Isaiah, chapters 56-66) which is made up of a collection of oracles. Scholars situate this portion of the book in the period after the Babylonian exile when the Israelites were allowed to return to the land and rebuild Jerusalem. Hence, this part of the book is reasonably cheerful and a favourite for Sunday mornings in church!

It’s a reading that sounds very nice and could easily pass us by, but this text situates itself in a much wider debate in the Hebrew Bible about belonging and identity.

v 6 ‘And the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord,

to minister to him, to love the name of the Lord…’

Here, we see something of third Isaiah’s radical vision of inclusion. The relationship between Israel and other nations is a fraught issue throughout the Hebrew Bible. Often it swirls around the particular issue of intermarriage, a subject about which many texts speak.

There is something of a ‘dialogue’ (read: argument) about intermarriage in scripture. The best example of this is found in the relationship between the books of Ruth and Ezra. Likely authored at a similar time, these books present intermarriage in ways which are diametrically opposed.

Ruth is presented in the text as the ‘ideal’ foreign woman. She recognizes the God of Israel from the beginning of the book and is eventually grafted into the people of God via her marriage to Boaz. Throughout, though, she is referred to as ‘Ruth the Moabite’ which keeps her foreign heritage front and center in the narrative.

This makes for a very interesting parallel text to the book of Ezra. Here, the people return to the land after their captivity in Babylon and begin to rebuild their lives and society. In chapter 9, Ezra learns that some of the people have intermarried with the ‘people of the land’ eg non-Israelites, and Ezra is horrified. In 9:3 he says ‘When I heard this, I tore my garment and my mantle and pulled hair from my head and beard and sat appalled’. Ezra subsequently demands that the foreign wives (and children) are sent away in 10:11.

All of this is against the background of the command to separate from other nations in the law. In Deuteronomy 7 we find a list of nations who are forbidden marriage partners, and Deut 23:3 states that ‘no Ammonite or Moabite shall come into the assembly of the Lord even to the tenth generation’. This is a particular problem for Ruth! Here, the prohibition is related to their lack of care for the people of Israel as they left Egypt, but against the wider background of laws like those found in Deut 7 we can see how in general, separation from other nations is strongly encouraged.

So what do we make of the idea in Isaiah 56:6-8 that foreigners are able to ‘join themselves to the Lord’, ‘to be his servants’, and even to be ‘joyful in my house of prayer’? This portion of Isaiah belongs in the same tradition as texts like Ruth, which seek to invite marginalized groups into the people of God.

It is, however, important not to demonize texts like Ezra and Deuteronomy. As Christians, the way we speak about the law can slip easily into anti-Jewish rhetoric if we are not careful. There is wisdom in being discerning about the things which we allow to influence our communities of faith, and these texts are concerned primarily with safeguarding the people of God.

When we come to the gospel though, we see the ways in which Jesus’ radical inclusion of outsiders was shocking and challenging to the culture in which we found himself. This inclusivity was not only challenging to the Jewish authorities but equally to non-Jewish groups in his environment. Jesus’ radical welcome was a shock to everybody and is foreshadowed in texts like Isaiah 56.

The optional portion of the gospel reading, Matthew 15:10-20 talks about the way in which ‘it is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person, but it is what comes out of the mouth that defiles’. This is, of course, a significant innovation on laws about uncleanliness, and thus one of the disciples reports to Jesus that ‘Pharisees took offense when they heard what you said’. But it is important for us to avoid the pitfall of saying that the Old Testament is legalistic and excluding and the New Testament loving and inclusive. Texts like Isaiah 56 show the opposite and point towards the greater welcome that Jesus offers to each one of us at his table today.