Although it is only Thursday I would like to take this opportunity to wish you a very happy new liturgical year!

What follows are some thoughts on the Old Testament reading for the first Sunday in Advent, Jeremiah 33:14-16:

14 The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will fulfill the promise I made to the house of Israel and the house of Judah. 15 In those days and at that time I will cause a righteous Branch to spring up for David; and he shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. 16 In those days Judah will be saved and Jerusalem will live in safety. And this is the name by which it will be called: “The Lord is our righteousness.”

This is a beautiful passage that has much to reflect on. Here are some thoughts to help you on your way.

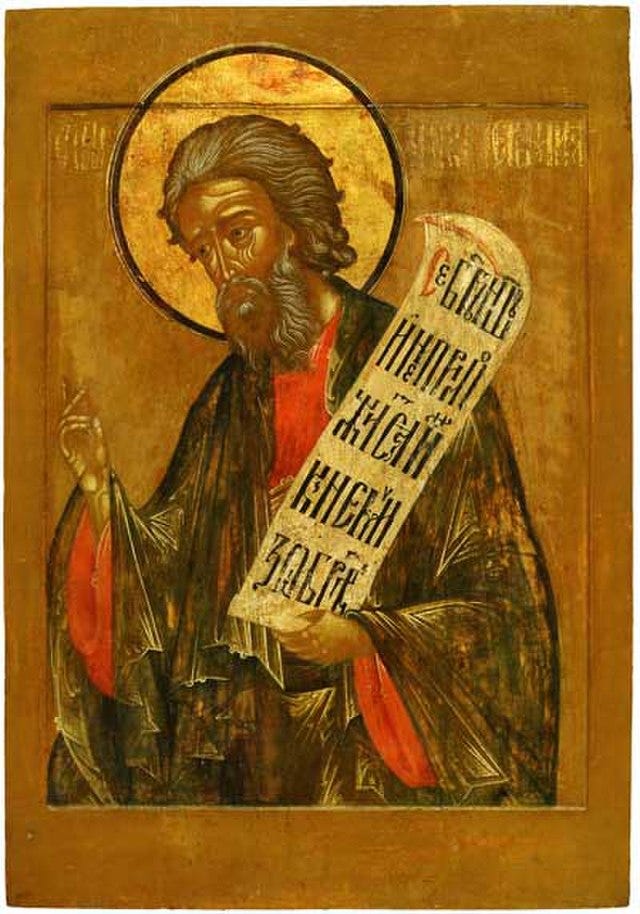

Korovniki church - prophet Jeremiah (c. 1654, Yaroslavl)

Wider context

Jeremiah is nicknamed the ‘weeping’ prophet on the basis that he is quite often found shedding tears in the book. In 9:1 he says

‘O that my head were a spring of water,

and my eyes a fountain of tears,

so that I might weep day and night

for the slain of my poor people!’

Jeremiah is one of the prophets of the Babylonian exile which we discussed a few weeks ago. Much of his mourning is generated by the lack of faithfulness that he sees around him which he frames as being the reason for the exile itself.

The text comes to a terrible climax in chapter 52:12-13 which describes the way that ‘In the fifth month, on the tenth day of the month—which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadrezzar, king of Babylon—Nebuzaradan the captain of the bodyguard who served the king of Babylon, entered Jerusalem. He burned the house of the Lord, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down.’

He goes on to describe the way in which many people were deported from Jerusalem but ‘Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard left some of the poorest people of the land to be vinedressers and tillers of the soil’ (v 16).

As an aside - there being people left behind in Jerusalem is an important piece of information to help us understand books that are about the return after exile. At the beginning of Ezra, for example, king Cyrus of Persia declares that the people may return to the land and rebuild the temple. When they get back, however, community dynamics become complex.

Who are the true Israelites at this time? Those who were left behind in the land, or those who experienced 70 years of exile? Much of the material in Ezra and Nehemiah grapples with these difficult questions of identity.

Immediate context

Returning, then, to our passage from Jeremiah. In a similar way to Lamentations, Jeremiah starts off sad, gets happy in the middle, then gets sad again by the end. This is one of the reasons that, historically, people wondered whether Jeremiah wrote Lamentations (though scholars would now say that he didn’t).1

Our passage comes from the ‘happy middle’ of Jeremiah, where everyone’s favourite most often taken out of context verse appears (Jer 29:11 ‘I know the plans I have for you…’)

Although as Christians it is important that we believe that God does indeed have good plans for us, which will prosper and not harm, it is also important that we set this passage in the above context.

Like 29:11, this Sundays reading emerges out of the context of national political upheaval and impending violence. It offers hope not just to those of us reading it today, but specifically to those who in the 6th century bce were staring down the barrel of what might have been the disappearence of their culture and destruction of their home.

‘A Righteous Branch’

One of the things which emerges the most clearly in this passage is a focus on ‘righteousness’. The Hebrew root צדק (tsedeq) appears three times in this portion of text and is usually translated ‘righteousness’ and is connected to blameless conduct and justice.

What, or who, then, is this righteous branch?

This is one of the passages from the major prophets which is often used in the season of advent as we prepare to receive Christ anew in the nativity story. It is read with him in mind and understood to have a prophetic tone.

As we know from the genealogy in the gospel of Matthew, Jesus did indeed ‘spring’ from the house of David, and so we can understand this passage as speaking prophetically of the coming messiah who would speak peace to those in Jerusalem and beyond.

It is also good, though, to try and put ourselves in the mind of the people for whom this passage was written. What kind of king were they hoping for? What might peace have looked like in their time?

Perhaps one of the reasons that righteousness comes through so strongly in this passage is because prophets like Jeremiah imagine that it is the unrighteousness of the people which led to the events of the exile. As I said in my exploration of Chronicles, though, we cannot always explain away suffering in such a straightforward way, and it is important that we can walk with people through it, without always needing to rationalise it.

The liturgy for morning prayer between allsaints and advent reminds us that ‘the darkness is passing away’. May this passage from Sundays lectionary guide us to having hope in the midst of the darkness and to look for the signs of God’s kingdom.

For further reflection:

What is the place of righteousness in the church today? How might we pursue it more deeply?

How can we hold in tension the historical location of this text and the ways in which it points to Jesus?

How do the themes of advent help us hold together the darkness of the present age and the hope that is to come?

Part of the reason for this is that in the Septuagint (Greek version of the Old Testament) the words ‘And it came to pass, after Israel was taken captive, and Jerusalem made desolate, that Jeremias sat weeping, and lamented with this lamentation over Jerusalem, and said…’ appear before Lamentations 1:1. This reflects a tradition of interpretation preserved by the writers of the Septuagint, but is not well evidenced. By 1966 Lachs states in his work that ‘most scholars have rejected Jeremiah’s authorship of Lamentations’ and this perspective has endured until the present day (Lachs, S. T., ‘The Date of Lamentations V’, The Jewish Quarterly Review, 57.1 (1966), 46 -56, p 47). See also: Berlin, A., Lamentations : A Commentary, 1st ed. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), Dobbs-Allsopp, F. W., Lamentations (Louisville: John Knox Press, 2002), House, P. R., and Garrett, D. A., Song of Songs, Lamentations (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2004)