Sunday Lectionary: The Book of Esther

The book of Esther is one of only two books in the Hebrew Bible that doesn’t mention God. 1 This is perhaps the reason I have never heard a sermon on the text!

This is a shame because the book has a great deal to offer. It is often thought of as a ‘feminist text’ because it has a woman at the center, but this is too simplistic. Esther is certainly brave and smart, but does that mean that the book pushes forward the cause of women? Is the book of Esther a saccharine picture of a brave heroine queen, or does it have a shadow side?

In order to explore these questions, we need to look at both the context and the content of the book.

Photo by Pro Church Media on Unsplash

Context

The story unfolds in the Persian city of Susa. The Persian empire, led by Cyrus the Great, overthrew the Babylonians. When this happened the people of Israel were able to return to Jerusalem, bringing the period of the exile to an end. Not all of them did so, however, meaning that there were Jewish communities living in diaspora in places such as Susa. Esther is such a person.

This context is important because it is the background against which the book works out questions of identity. In a city like Susa, the Jewish community would have been a minority who had to work hard to preserve their collective identity in a context enormously different from where that identity was initially formed.

This is one of the most significant struggles related to the exile in general. Exilic and post-exilic Biblical texts are often wrestling with questions about what it means to be the people of God in a different context.

It is often suggested that the King figure in the book of Esther is Xerxes I, who reigned between 486 and 465 BCE. This was a long while after the Babylonian exile, which happened in 586BCE. So, although the people living at this time would not have had first-hand experience of the exile, it lived on as a significant event in the life of the people and played a significant part in their communal identity.

Content

How do these dynamics play out in the story?

The portion of the text set for this Sunday features Esther requesting that the Jews who live in Susa be spared from death. Haman, the pantomime villain of the book, has plotted to kill the Jews of the city, but by winning favor with the king Esther prevents this disaster. In a darkly comedic turn of events, Haman is executed on the very gallows he built for Esther’s cousin/uncle (the text is unclear) Mordechai who was a significant figure in the Jewish community.

On one level, then, the text presents a situation in which a significant power (Haman) threatens the lives of the Jewish people in Susa. The picture of a minority group being threatened by a significant power has important parallels with the exile itself.

Another in which we can see exilic themes in this text is in the figure of Esther herself.

In many ways, she is a remarkable figure. She bravely advocates for the lives of her people, putting herself in immense danger. She is articulate and intelligent in her engagement with powerful figures. As Sorrell Wood has recently pointed out, she is one of only two women in the Hebrew Bible who are depicted as writing.2 Details like this help us to see Esther as a skilled and able individual.

On the other hand, scholars have recently begun to probe the problematic nature of the beginning of the story. Here, Esther is presented to the King amongst many other young virgin women, from whom he selects women to join his harem. In her work on the text, Erica Dunbar has recently explored whether the process depicted at the beginning of the book reflects something of modern-day human trafficking. As she states;

The opening chapter of Esther introduces problematic gendered relationships between the male and female characters, as Vashti is deposed for resisting the king’s demands that she display herself before his drunken party guests

She goes on to describe the way in which women in the text are ‘expendable’ and ‘commodifiable’. 3 Esther avoids this reality, only because she is able to leverage her beauty to gain the favor of the king. This does not take away from the fact that she is wise and articulate, but she perhaps would have been without the opportunity to demonstrate that if she were not also beautiful.

There is a shadow side to the book of Esther, which makes it more than a story of a victorious heroine. Throughout the story, Esther is vulnerable. If she puts a foot wrong she, like Vashti, might have found herself banished (or worse). Nevertheless, she demonstrates boldness and the willingness to sacrifice herself for the sake of others.

I have never heard a sermon on Esther, but that does not need to be the case for others! This Sunday, how might we draw on the story of Esther to reflect on boldness and sacrifice in the face of vulnerability?

What I’m Reading

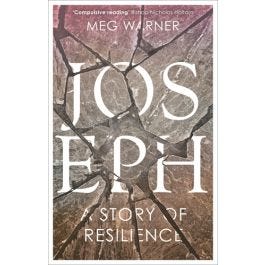

Joseph: A Story of Resilience by Meg Warner

Here Warner brings together insights from trauma studies to the Joesph narrative, as she explores what we can learn from both about the task of resilience. This is an excellent read from which I’ve learned new things about the Joseph narrative, as well as reflecting on my own ability to be resilient. I highly recommend this!

The other is Song of Songs

Wood, Sorrel. "Writing Esther: How do Writing, Power and Gender Intersect in the Megillah and its Literary Afterlife?: " Open Theology, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 35-59. https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2020-0146 - this is open access, so you can read it for free!

Dunbar, Ericka S, ‘For Such a Time as This?# UsToo’, Bible and Critical Theory, 15.2 (2019), 29–48, p 44 - also accessible for free