The Book of Ruth: Part 1

Idyllic pastoral tale of love or something more Grimm?

The book of Ruth, which is currently in the lectionary for morning prayer, is almost universally loved amongst readers of the Hebrew Bible. Often, it is presented simply as a pastoral idyll, a heartwarming love story made up of sweetness and light.

But is this the whole story?

In this newsletter, which will be the first of two installments on Ruth (part 2 will arrive next week), we will look again at the text and pay particular attention to its more ambiguous elements.

By asking questions of the text which we might previously have overlooked, we will uncover more of the complexity of the text and allow it to expand beyond the saccharine sweet fairy story that we might have seen it as before.

[In what follows there is a brief description of non consentual sexual contact, so skip to the painting of sleep beauty if you’d rather to avoid that.]

Hayez, A Woman as Ruth: 1850 (Wikimedia.commons)

Ruth is not a Fairy Tale

To begin, we’re going to take a brief detour away from the Biblical text…

Most of us will be aware that there are two versions of ‘sleeping beauty’.1 The most recent, and probably most familiar to us is the Disney version of the fairytale (imagine a screengrab here - I can’t include one because I don’t want to be sued by Disney for copyright infringement…).

The second is the original tale by the Brothers Grimm, upon which the Disney version is based. This version of the story is much less idyllic. It is creepy and at times disturbing.

Primarily this is because the unconscious ‘sleeping beauty’ figure is made pregnant by the king while unconscious without her consent, and only becomes aware of this fact when she awakens to find she has given birth to twins. The rest of the story is described in this article.

Sleeping Beauty, by Henry Meynell Rheam, 1899

These more troubling aspects of the story are, however, stripped away from the Disney version, leaving a story which is entirely unproblematic and suitable for five-year-olds.

Sometimes, we are tempted to do the same to the book of Ruth. We read it through a Disney lens, as a perfectly idyllic love story where poor Ruth is rescued by a dashing suitor who just so happens to double as a Christ type (because, of course, there’s no one else in the story that could fulfill that role but the man…despite Ruth’s self-sacrificial behavior throughout).

But really, the detail of the text shows us that the book of Ruth is more Grimm than Disney.

There are many layers of complexity in this text, particularly in relation to the motivations and behaviors of the characters involved. When we take this into account we find that there are some very ambiguous aspects of the text which challenge the understanding of it as a straightforwardly idyllic folk tale.

Here are some questions we can ask about the text which highlight what I mean:

When Naomi allows Ruth to go out and glean for the both of them, is she putting Ruth at risk of violence in the harvest field? See her warnings and those issues by Boaz in 2:9; 2:15; 2:22

When Ruth gives birth to her son Obed at the end of the book, the text says that Naomi takes the child and becomes his guardian (using the word for an adult who takes sole responsibility for a child as per Esther 2:7 and 2 Sam 4:4). Why should this be the case, when his mother is depicted in the scene with him?

What should we make of the deliberately ambiguous descriptions of the events at the threshing floor in ch 3? How far might Ruth have been willing, or encouraged, to go in order to secure her marriage to Boaz?

These are just some of the questions we might ask about Ruth in order to go beyond a simplistic reading of the text. Others are concerned with whether Ruth and Orpah were willing participants in their marriages to Mahlon and Kilyon, as explored in this blog post by Rabbi Deborah Kahn Harris (Content warning: violence against women).

When we flatten the book of Ruth into something like a fairy story, we miss out on the nuances of the text. By asking questions like these we uncover some of the more complex aspects of the narrative.

The presence of these shouldn’t surprise us too much, given the wider context of the book. Ruth and Naomi are trying to find ways to escape food poverty and starvation. It is still true today that precarity can push people to do things they might not otherwise have done.

Does this mean that Naomi was manipulating events and exposing Ruth to danger for her own benefit so that she might eventually take her child away so as to replace one of her dead sons? Not necessarily! But by asking these questions of the text we reach a more well rounded understanding of it rather than reducing it to a shallow version of itself.

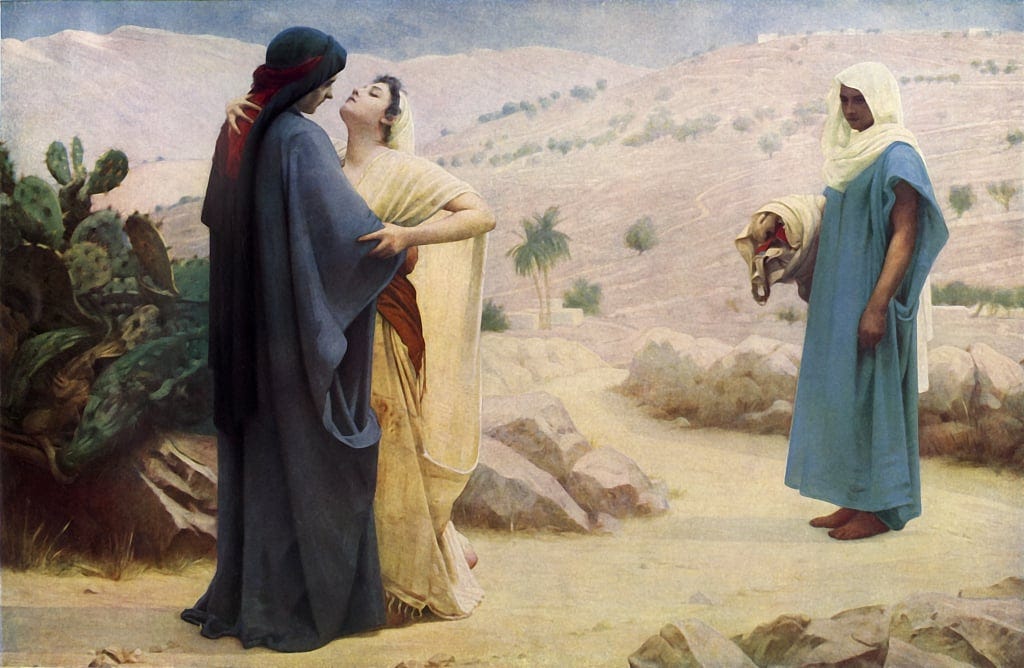

Philip Hermogenes Calderon - Ruth and Naomi 1886 (wikimediacommons.org)

That being said, there are certainly some idyllic, or at least aspirational, aspects of the text. For one, all of the problems which the women face at the beginning of the narrative (food poverty, lack of protection provided by a male-headed family unit, childlessness) are resolved by the end. In that way, it lives up to the pleasant folk tale it is often conceived as.

Further to this, Ruth is undisputably a remarkable figure. She is described as a אֵ֥שֶׁת חַ֖יִל ‘eshet chayil’, meaning women of strength or valour in 3:11. This is the same phrase as that which is used of the woman in Proverbs 31. This is more than a designation belonging to a ‘good wife’ because the root חַ֖יִל is related to words like ‘strength’ ‘wealth’ and ‘army’. This phrase refers to a person who is strong, capable, and wise.

Further to this, the root חסד which is often translated ‘loving-kindness’ and is used to describe God’s love and faithfulness towards Israel appears throughout the book. It is used to describe Ruth’s actions and to refer to God, which demonstrates the extent to which her strength was in how she related to those around her.

But, as we have already explored, there are aspects of the text which indicate that Ruth’s goodness and faithfulness meant that it was possible to use her for their own advantage. Some readings of the text take a more cynical view of Naomi’s motivations, whereas others consider their relationship to be a shining example of covenant friendship in the Bible. The thing about Ruth is that there is material in the text which supports both positions, and this is in part what makes it an interesting book.

Rather than flattening the book to fit within one perspective over another, let’s try to hold together the complexity of the narrative and be open to all it has to teach us about human nature and God’s provision.

Maybe even more than two! But this is not my area of expertise so I’ll leave that speculation to someone else…