Greetings all! Apologies for the gap between newsletters, during lent I was trying to finish my PhD which required all of my brain power. I submitted it last week, so normal service will resume again now!

I’m aware that various people made use of the lent course on the Psalms. If you did use it, would you mind clicking this link to let me know? There’s also an opportunity to offer feedback if you’d like to. Thanks to everyone who engaged with the resources!

Over the last week or so, the morning prayer lectionary has given us readings from the book of Deuteronomy each day.

Deuteronomy is a fascinating book with a very distinct character. It also raises lots of questions: how should we read it? What genres goes it use? What are the key issues it addresses?

So that we might better understand what we’re reading, here are a few key things that we need to know about the book. We’re going to look briefly at the structure of Deuteronomy and its theology, with a particular focus on justice for the marginalised.

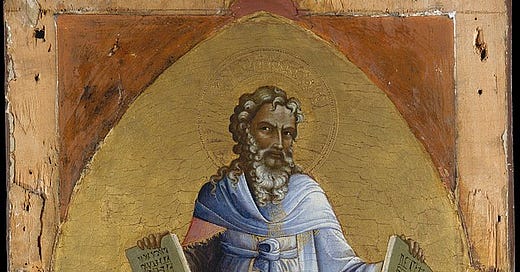

Moses, Lorenzo Monaco, circa 1408 –10

The book of Deuteronomy has two distinct parts, the ‘law code’ (chapters 12-26) and the ‘framework’ (chapters 1-11 and 27-34). The framework is largely in narrative form, and picks up the story where it left off in Numbers. There is a particular focus on Moses, and his exhortations to the community as they are on the cusp of entering the promised land.1

The law code, called the 'Deuteronomic Code', is one of three that we find in the Hebrew Bible. The others are the Covenant Code which is found in Exodus 19-242 and the Holiness Code which is found in Leviticus 17-26.

The Deuteronomic Code largely revises the laws of Covenant Code found in Exodus, meaning that there is a lot of crossover between the two. What is interesting, though, are the revisions that the writer(s) of Deuteronomy chose to make. Here is an example from my research…

Both Exodus and Deuteronomy contain laws about festivals, how they should be celebrated, what should be offered, and who should be involved. In relation to Shavuot, or the Feast of Weeks, Exodus says this:

You shall observe the Festival of Weeks, the first fruits of wheat harvest, and the Festival of Ingathering at the turn of the year. (Ex 34:22)

Deuteronomy, on the other hand, goes into much more detail. In relation to the same festival, it says:

9 “You shall count seven weeks; begin to count the seven weeks from the time the sickle is first put to the standing grain. 10 Then you shall keep the Festival of Weeks to the Lord your God, contributing a freewill offering in proportion to the blessing that you have received from the Lord your God. 11 Rejoice before the Lord your God—you and your sons and your daughters, your male and female slaves, the Levites resident in your towns, as well as the strangers, the orphans, and the widows who are among you—at the place that the Lord your God will choose as a dwelling for his name. (Deut 16:9-11)

Here, we see something which is a key pattern in the book and a significant part of its theology - an emphasis on including the margnalised.

Deuteronomy makes reference to the widow, the orphan and the alien more than any other book in the Hebrew Bible. All the way through the law code, like in the example above, there are references to these groups being included in the life of the community. As well as this the law contains frequent reminders that these ground should be treated justly.

The theology of Deuteronomy is, then, very much concerned with justice. In the law, the people are told to do right by the marginalized. The material in the framework, which was likely a later addition, expands on the theological foundations of this. Deuteronomy 10, for example, says:

17 For the Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe, 18 who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing

The book argues that the people must be just because God is just, and also lays out the consequences if justice is neglected.

There are many other theological strands to Deuteronomy, but next time you are reading the law and wondering what it’s for, consider the importance of justice in the book.

For a good discussion of issues related to authorship, I would recommend the introduction to Richard Nelson’s commentary (Nelson, Richard D.. Deuteronomy: A Commentary (London: Westminster John Knox, 2004.) which can be accessed for free on Google books

This is a contested issue, some scholars would say that the covenant code should be restricted to chapters 20-23, so you will find differing views in different commentaries